October

24

October

24

Tags

The Bicycle Helmet: to wear or not to wear?

Debating whether helmet laws save lives or discourage cycling

From my column in the Washington Times Communities

WASHINGTON DC, October 24, 2012- Last month, a friend and cycling blogger sent me an article and asked me whether I wore a helmet when I rode my bicycle. I said that I did wear a helmet, but the truth is, I should have said I wear one most of the time, depending on the ride. And, if personal experience and observation holds, a lot of people do the same. The question of whether to wear or not to wear a helmet is heating up, with strong arguments on both sides.

There is no doubt that if you are in a bicycle accident involving a head injury, a helmet may very well save your life or prevent brain damage. Many argue however, that while there is a very small chance of being in a bike crash involving a head injury, forcing people to wear helmets discourages mass-ridership, which in turn would save far more lives by preventing heart disease, obesity, diabetes, etc. than bicycle helmets ever will.

This is a tricky proposition. It sounds like the question of whether it is permissible to sacrifice one life to save many. The truth is that bike accidents do and will happen. Some riders will be severely injured and even killed. Helmets will prevent many of these injuries and save lives. On the other hand, it is also true that fatalities are rare and many studies show that compulsory helmet use discourages ridership.

Before you hit the comment button, read on.

A Bike helmet can save your life

It cannot be argued that a bike helmet is indispensable and could save your life IF you are in a bicycle accident involving head trauma. A helmet does not guarantee, however, that your life will be saved if you are in a bike accident, especially if the accident involves body parts other than the head.

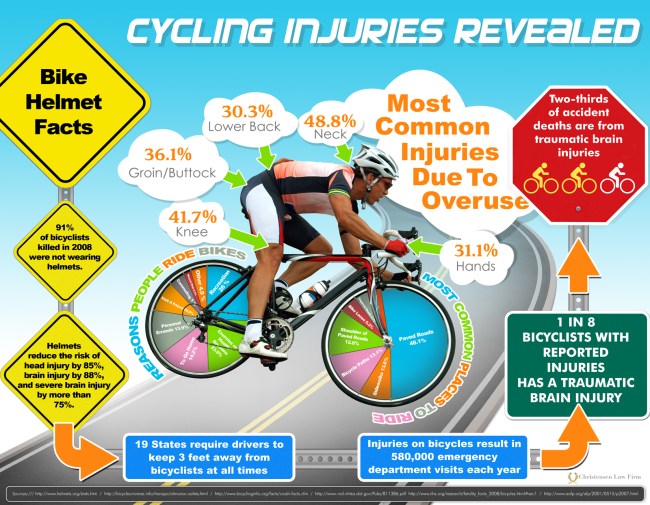

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA) 2008 Traffic Safety Facts, 70% of cyclists involved in a fatal crash suffer from head injuries, and helmets are 85 to 88% effective in preventing head and brain injuries. The NHTSA calls helmets “the single most effective way to reduce head injuries and fatalities from bicycle crashes.”

US v. Europe

All major organizations that have anything to do with health, safety, and transportation in the US advocate the use of bike helmets all the time. This is turn has created a cultural philosophy around bike helmets. Basically, if you don’t wear a bike helmet you’re perceived as antisocial and reckless. In the US, not wearing a helmet while riding your bike is like smoking or talking on your phone while driving your car.

Personally, since I started riding as an adult only recently, I never questioned the helmet mentality. When I thought about wearing a helmet, I associated it with wearing a seatbelt: annoying but stupid if you don’t do it, and pretty soon you forget about it and it becomes second nature.

For this reason a little less than half of US states and the District of Columbia have enacted some form of bicycle helmet legislation. According to The Insurance Institute for Highways Safety, 21 states and the District have a bicycle helmet law. A list of all states with bicycle helmet legislation can be found here.

The situation is very different in Europe. France, Italy, Germany, the UK, and Switzerland have no mandatory helmet use laws. Other European countries have helmet laws for children. However, there does not seem to be a higher rate of cyclist fatalities, and all of these countries have high ridership and mature cycling cultures and structures. In major European cities and towns, the focus is not on helmet use but on providing a safer cycling infrastructure and slowing or prohibiting traffic completely around city and town centers.

Now on to the more controversial proposition.

Fatalities are rare

While it is true that a helmet may save your life or prevent serious head and brain trauma, statistics show that cyclist fatalities are relatively rare. According to the NHTSA’s 2009 Traffic Safety Facts, there were 630 cyclist fatalities involved in traffic accidents during that year in the US. This accounts for less than 2% of all traffic fatalities. Additionally, for the same year 51,000 cyclists were injured in traffic accidents, which also accounts for 2% of the total injuries in traffic accidents.

Compulsory helmet usage discourages ridership

Several studies suggest that making helmets compulsory will discourage many people from riding a bicycle at all, which in turn will cause more deaths through diabetes, heart disease and obesity than helmet-less accidents. Less riders also means that it will be more difficult to build up a safer cycling network and reap the benefits of mass-ridership.

The fear factor

Proponents argue that aggressive helmet use campaigns and promotion makes a relatively safe activity seem a lot more dangerous than it really is, and this, in turn, turns off a lot of potential riders.

According to many scientific and not so scientific studies, the single biggest factor that discourages people from riding their bike more is fear. The argument goes like this: while cycling is statistically as dangerous or less than walking down the street, stepping into your tub, or climbing a ladder, when asked to wear special “body armor” to cycle, a large number of people will perceive it as more dangerous than it actually is and will refrain from doing it altogether. According to the European Cycling Federation, cycling is just as dangerous as walking per mile traveled; yet people are not asked to wear a helmet to walk down the block.

There may be some truth to this claim. I, for one, was terrified of riding my bike in the city and it took me literally years to work up the courage to do it. I’m not sure my fear was completely tied to the fact that local wisdom says you should always wear a helmet and that made me fearful of riding, but after two years, I can honestly say that it is far less scary than I initially perceived, and I wish I would have done it sooner and not been so frightened.

Helmets & Bike -sharing

There is also the issue of trying to develop a safe cycling network, a big part of which has become the development of a robust bike- sharing program, which in turn may be at odds with compulsory helmet laws. There is evidence that a city bike-sharing program is more likely to be popular if that city allows riding without a helmet. Mexico City seems to agree, as it recently repealed a mandatory helmet law before inaugurating its bike-sharing plan.

The DF may have learned from other cities. Consider Melbourne, Australia, with a compulsory helmet law and a bike-sharing program with an average of 150 rides per day. Compare this with Dublin, Ireland, where bike helmet laws are relaxed and their bike-sharing program has an average of 5,000 rides per day. While there may be other factors that account for this difference, it is important to note that while Dublin is full of hills, has cobblestone roads, and cold and rainy weather, Melbourne is flat, has wide paved roads, and mild weather. Consider also that Melbourne’s population is 4.1 million, while Dublin’s is 1.2.

Major American cities are also foregoing compulsory helmet use for adults in favor of growing their bike–sharing programs. DC makes helmet use compulsory for children under 16 years of age. A recent Georgetown study found that around 70% of those who use the city’s wildly popular Capital BikeShare do not wear a helmet.

Similarly, New York has failed to enact a compulsory helmet law, even as the city awaits the opening of its own 1,000 bicycle bike-sharing program in 2013. However, New York City is pursuing an aggressive education and free helmet programs to encourage helmet use.

The special case women

In her article, Elizabeth Rosenthal quotes European researchers as saying that “ the test of a mature bike-sharing program is when women outnumber men.” However, in most, if not all North American cities male riders outnumber females, sometimes 2 and even 3 to 1, both on bike-shares or private bikes (there are exceptions, of course). In the US, women accounted for only 24% of bicycle trips taken in 2009, according to The National Household Travel Survey.

The same is not true in other countries where helmet use is not compulsory and not so aggressively promoted. In the Netherlands, for example, women account for 52% of cyclists. In Germany female ridership is 49%. European cycling proponents suggest that more women ride in Europe because these countries focus on providing safer bike lanes and slowing traffic in city centers rather than promoting helmet use.

Why do women ride less in the US?

According to Ell Blue in “Bicycling’s Gender Gap,” the most often cited reasons why women don’t cycle more are fear and fashion. Even though Blue’s article goes much deeper into exploring the real – economic – reasons why women don’t cycle, fear and fashion also have a lot to do with helmet use.

As discussed above, compulsory helmet use and aggressive promotion may discourage many women from riding by making cycling seems more dangerous than it really is. Linda Baker’s “How to get More Bicyclists on the Road” suggests that women are a kind of “indicator species” of a safe and mature cycling structure because women are more risk-averse than men. If helmet promotion makes cycling seem like it presents more risk than it really does, more women than men will refrain from doing it at all. On the other hand, according to Baker, if more women ride, their risk aversion translates to a demand for a safer and more comprehensive bike infrastructure (what you see in Europe).

Fashion has also been cited as one of the reasons women do not cycle more. It may be difficult to wear professional attire and arrive at the office smelling fresh if you have to cycle 20 miles. The same can be said for a date or lunch with friends. However, for women who travel shorter distances, having to wear a helmet could be a deciding factor on whether to commute by bike. Let’s face it; you cannot get to the office or an important meeting with a helmet head, so instead many professional women forego riding altogether.

So, to wear or not to wear your helmet?

Compulsory helmet use for children is a no-brainer. Of course they should wear a helmet and I have no problem with legislation making helmet use mandatory for minors. However, the more I learn about the subject, as well as from personal experience as a novice city rider, the more unsure I am about whether I need to wear one all the time.

I have a confession to make. I don’t wear my helmet that much.

After two years of riding every day to pretty much the same places, I must admit, I don’t wear my helmet every time if the ride is a few blocks and there is a bike lane route. I’m lucky that I live in DC and in a neighborhood where almost every other street has a bike lane and traffic is relatively light and slow. I also work from home.

My gym is .6 miles away and I don’t wear a helmet when I ride there. I don’t wear one to go to the store three blocks away, or when I go out to dinner in the neighborhood with my husband. On the other hand, I wear a helmet for longer rides or any ride that takes me where a bike lane will not. I also always wear one when I go on a fitness ride. But near home, no, I don’t wear my helmet. If I were forced to, I probably wouldn’t ride as much.

There, I said it. I feel like I just admitted to killing a puppy…

To be on the safe side, I still advocate wearing your helmet every time. As John Kraemer, assistant professor of health systems administration at NHS says in the Georgetown Study,

“Bikers can’t always control the environment around them, but they can control whether they wear a helmet.”

But it does make you think…

Go back to Cycling

Related articles

- Study Shows Bicycle Helmets Save Lives – U.S. News & World Report (drugstoresource.wordpress.com)

- Cyclists without helmets three times more likely to die of head injuries (gjnashen.wordpress.com)

- When Did Having a Death Wish Become the Cool Thing to do?(shampoosviews.com)

- Vancouver cyclists say rash of bike helmet fines wrong way to encourage ridership (theprovince.com)

- To Encourage Biking, Lose the Helmets (tech.slashdot.org)

- Unique & Fashionable Hand-Painted Bicycle Helmets by Belle Helmets (laughingsquid.com)

- Will Easing Bike Helmet Laws Up Ridership? (news.health.com)

- You Wear a Helmet, Don’t You? (chasingmaiboxes.com)

Very nice and interesting piece. I love riding. When I learned to ride I started out wearing a helmet so it is almost automatic for me to reach for my helmet and ask others where is their helmet if I see that they are not wearing one. I almost feel naked without it.

Thanks, Cheryl. It took me a while to admit I don’t wear one, but that is only for short rides. If I plan on going for more than 5 blocks, I wear mine too. Do you ride in the city? For commuting or exercise?

Great Article. The issues are well laid out. I agree children should always wear helmets.

I have lived overseas working for US DoD agencies mostly around US Army installations. On these installations there are regulations mandating that all personnel, military, civilian and their families wear helmets on installation while riding their bikes.

My most recent position was working at a DoD school where both children and adults would bicycle to the school daily. Some came with helmets some did not.

Mandating helmets through regulation did not incentivize into them wearing helmets. Most did not know about the regulation. When I would explain the regulation it would not effect a change to wearing helmets.

My perception was if the person had concern for personal and/or family safety, helmets were on.

I agree that children should wear helmets, and parents should as well if they want to set an example for their kids. I think that once I have a child or if I am ever in a position of being around many children, I’ll have to start wearing a helmet all the time, and I’ll do so gladly! Thanks for your input!

I am from Australia (where wearing bike helmets is compulsory), and live in the Netherlands where it is not. The two countries are very different in terms of infrastructure, weather and opinions on bike travel.

Australian (like US) cities are urban sprawls, connected by major roads with little bicycle infrastructure. Distances are greater to travel, and the perception of car drivers is different. Roads are for cars. Furthermore, it is often hot in Australia (which is not often the case in Holland), which makes me, an avid cycler, opt for the car. I opt for the car, on these occasions, because I don’t want to wear a helmet, sweating profusely with the helmet on.

In Holland, cycling is almost the default mode of transport. There are separate cycle lanes on main roads and cycle paths, miles away from cars, passing through the forests and fields with cows. Cyclists are allowed to go down one-way streets in the other direction, and turn where cars are not. I can ALWAYS get from A to B faster if I cycle than if I drive (inside my home town). Admittedly the town is not a vast urban sprawl, but, trips of less than 3 miles are faster cycling. In Holland cars watch out for cyclists, and the whole experience is much safer. I don’t experience cycling as being dangerous.

I think the dangers of cycling without a helmet are dwarfed by the health advantages, as well as the benefits for the environment. Also, not having a car saves me 1000s each year in insurance, taxes, repairs and gas. Compulsory helmets do prevent many people from cycling. Combining the removal of compulsory helmets with better cycling infrastructure is the way to go!

Great points! I agree and DC is the same as Holland- anything under 3 miles is WAY faster on a bike. When I do take my car, I’m always sitting in traffic thinking “I’d already be there if I’d taken my bike…” I love the cycling culture in the Netherlands. Last time I was there I was distracted walking down the street and almost got run over by a bike! I think every tourist has that story to tell of the Netherlands- but it speaks to how much you guys use your bikes- which I admire! RIDE ON, Lambchopeindhoven!

great post, i use a bicycle in central London for work when i can and i always wear a helmet. i have also ridden a scooter for work and have come off it a few times and having had the experience of sliding along wet tarmac and using my head and shoulder to stop on a kerb stone i can say wearing a helmet will save your life. i still ended up with a badly bruised shoulder and knee. but my head was fine. the helmet did its job. although cycle helmets are less protective than motorcycle helmets it’s better than nothing. PRACTICE SAFE CYCLING!

Mark, you are so right and your comment makes me think…maybe I should wear my helmet more often… My husband had a wreck a few months ago with injuries that sound similar to yours. He wasn’t wearing a helmet and besides a nasty shoulder gash, luckily just had a scratch on his scalp. Now he wears a helmet almost all the time. Maybe I’ll start wearing mine on just one of my daily errands and see if it sticks…Thanks for your comment and cycle safe!

I agree with almost everything you’ve said. I personally wear a helmet all the time (it’s the law in BC), but wish the government would scrap the mandatory helmet law. Vancouver is trying to introduce a bike-share program, but the mandatory helmet law is the biggest obstacle to the roll-out and ongoing success of the program.

I do find it curious that many bike advocates have come out against helmet laws for adults, with well reasoned arguments that you summarized so well, but are dogmatic when proposing helmet laws for kids. Why wouldn’t all of the same arguments that apply to a 30-year old apply to a 16-year old? Childhood obesity is at epidemic levels, teenagers are often more fashion-obsessed than adults, and mandating helmets for kids creates a culture of fear that discourages kids (and pressures their parents) so they don’t ride their bikes to school. So, why do rational people come to the conclusion that a helmet law a bad idea for adults but a good idea for children? Are we supposed to take arguments like “compulsory helmet use for children is a no-brainer” on faith?

I think you are right about the risk for children, but what I think is that while adults have the maturity to understand and undertake the risks of riding without a helmet, children do not…

Isn’t that why children have parents? You mentioned the ECF stat that cycling is as dangerous as walking, and we don’t require walking helmets. Wouldn’t the same apply to children? Should children wear helmets while in playgrounds? There are lots of chances to fall and hit their head. At what point are we going to far? This over-protection of the “bubble wrap generation” isn’t healthy.

I agree, but I think with children, they are a lot less experienced on bikes, probably tend to be less safe (from lack of experience), and their little heads are probably more fragile than my thick skull!

low tree branches force me to wear a bicycle helmet out here lasesana

I’m jealous! Your pics are fantastic!

why thanks i hope you click like them

Reblogged this on bikeworldusa and commented:

As my uncle and owner of BikeWorldUSA’s sister company Freemand Bridge Sports always says… “You can fix a broken bone, but you can’t fix a broken head.”

Very true…

A very thought provoking article. It is a debate that rages here in Australia, and I’m sure elsewhere around the world. Personally I wear one always having been involved in a cycling accident many years ago, prior to the time that helmets were compulsory in Australia. Perhaps it should be left up to the individual, but how to you then tell children they must wear one, but it is okay for adults not to? Either we all need one, or we don’t?

I think that as adults we can understand the risks of not wearing a helmet and undertake that risk knowing the consequences. Children don’t have the same experience or understanding and therefore should always wear them until they are old enough to make a mature decision. However, I understand how this may look hypocritical. I think that if I have children or if I am in a position where children look at me as a role model, I would have to wear a helmet…

By the way, I love Australia. I was there for 6 months in 1999, and will never forget it.

Come back,we love having visitors! 🙂

I will, definitely on my list- Byron Bay is still one of my favorite places on earth!

Thanks for following me. God bless you! 😉

This is my first read of yours and I like your thorough approach to this topic. The poll needs “Most of the time” as I am in that category. I wear a helmet most the time I am thinking about riding a bike. That’s sick, I know. If I am riding around the block, no. The thing is that I don’t like to go over 15 mph without a helmet on and the yen does strike me even on a jaunt around the block. Add to that almost 20 years of commuting by bicycle, a helmet saving my tiny brain more than once, and I see the wisdom of wearing a helmet even when thinking about riding.

I’m kind of in the same boat, and I never go over 10-12 mph without a helmet. 20 years of commuting by bike, huh? You are one of the pioneers!

20 years commuting. Until recently there were not a lot of people commuting by bike out in the western Chicago burbs. I rarely saw another cyclist. Now it is very common. The first few years were the learning years, when a lot of motorists (even old ladies) got upset with me simply because I had not learned proper etiquette. Now I rarely have a negative encounter, partly due to what I have learned and largely due to more familiarity by motorists with cyclists.

I know! A few years ago, there were a handful of cyclists on the street at one time- now its bike rush hour every weekday morning outside my house. I also agree that it takes some time to learn the etiquette of riding, because its not just motorists who have to learn to share the road!

Really interesting article – thanks for this! (and thanks for following my blog!) In the UK i didn’t really like using a helmet and would often go out without it, though this was a fair few years ago. Here in Brazil there is pretty much minimal respect between cars and riders so I won’t leave home without it now.

In Brazil the better helmets are quite expensive which can put some people off (but comfort and air-circulation aside, would a cheap helmet give you as much safety protection as an expensive one..? have often thought about that…) – got new a helmet in the US which would have cost the earth here and it is definitely more comfortable/lighter… simply nicer to wear than the climbing helmet that had been using, so really even less excuses not wearing one now!

I see you are originally from Colombia – do you go back there often, and how is cycling there? I have been in Bogotá which I really enjoyed, though (Sunday aside when they closed off half the roads to allow cyclists) traffic didn’t seem too friendly to bikes…

Can envisage a scenario outside of city in areas that have much less traffic where I might take the helmet off, but I guess it is a habit now. And afterall, I guess, we never know when an accident might happen.

Thanks for reading! I can see how you would always wear a helmet in Brazil, as the traffic sounds a lot like traffic in Bogotá, where, as you said, aside from ciclovía, riding your bike can be a little dangerous. A close friend has a blog about cycling in Bogotá: http://theturningwheels.tumblr.com/post/31984719134/bogota-es-d-c-distrito-ciclero which I read often. I think that Bogotá, as many other cities, is becoming increasingly bike friendly, but has a ways to go. I saw an interesting article- when I find it I’ll post a link- about women and how they are an indicator of a safe bike structure (mentioned above) and how in Perú women make up only 2% of cyclists. I would assume the numbers are similar in Colombia and Brazil.

Your comment about helmets is interesting- it is a real problem that people in poorer countries do not have access to moderately prices helmets- especially when you consider that the poorer countries is where they are needed the most because they often lack the safe bike infrastructure. I’m wondering if we can get together and do something about that- maybe get my cyclist friends and readers here in the US to donate their old helmets and get them over to you in Brazil and you can distribute them to people who need them… It may be a bit of work, but I’d be willing to discuss if you are!

Thanks for pointing me to your friend’s blog – interesting read. I guess it is ultimately an evolution in attitudes of vehicles drivers and cyclists, with drivers getting used to increased numbers of cyclists – a slow slow process! At the same time, though, we see plenty of cyclists here who don’t know how to ride safely with cars around them…

Could be interested in working with your idea about helmets… Decent bikes are expensive in São Paulo, so people who can afford them would normally be able to get a helmet. Poorer classes, however, here and outside of the city could definitely benefit.

Coming back to the point about riding safely, however, I think that educating riders about safe riding would be a good base to start: I remember in the UK, at around 9 years old, we all took a “cycling proficiency” course where we were taught basic cycling safety standards. There is nothing like that here. I think developing a program like that here for schools (say with the public schools for free) – where perhaps helmets could be given to people who do well in the course – could be a very interesting idea… Will speak with people to get their feedback – navigating bureaucracy with public systems (as you can imagine!) here can be quite frustrating, though.

This education course could definitely be extended to the private schools as well – there is as much “bad cycling” from the wealthier people here as there is with from poorer classes, and also kids are growing up never cycling at all and seeing adults driving paying little respect to cyclists – if they at least have awareness about how it is riding a bike, then perhaps this could be great for the long term safety of everybody…

Reblogged this on 360 Extremes Expedition and commented:

With the previous close shave we had with Natalia (http://360extremes.com/2012/11/22/accident-avoidance/), this is a great article from Lasesana about whether or not to wear helmets. Both Natalia and I wear helmets all the time (though had the truck hit Nat this time, am not sure if it could have done much to help… again, a frightening thought). I think in Brazil, and especially in the cities, it makes a lot of sense. However, we know plenty of people who don’t… Have a read and see what you think.

Lasesana, I just visited your blog after you tagged mine, thinkbicyclingblog.wordpress.com, and I agree with much of your observation.

Personally, I ALWAYS wear a helmet, even on the shortest ride, not because I think I’m likely to fall and hit my head, but because I don’t want NOT wearing it to come back to haunt me, i.e. “He calls himself a bike educator but doesn’t wear a bike helmet?!” That’s a consequence of the excessive focus on helmet wearing in the U.S., to the near-exclusion of bicycle education, to be absurd and counterproductive, in the ways you list.

However, you mention bicycle lanes positively above and I would disagree on that point.

After 40+ years as an adult on-road bicyclist and certified cycling instructor, my views on what makes cycling safe have evolved from promoting segregated bicycle facilities when still living in England, to firmly believing that what is most important is soundly-based age-appropriate bike education. An excellent example of an adult program is CyclingSavvy (see http://cyclingsavvy.org), started by Keri Caffrey and Mike “Mighk” Wilson, in Orlando, FL, and now spreading nationwide.

For children, I’ve posted a curriculum on my blog at http://tinyurl.com/6v6cs5z. It was originally created and taught as an in-school P.E. elective to 13-year-olds in Palo Alto, CA, middle schools by Diana Lewiston, a very experienced and gifted cycling instructor.

Martin, I agree, age-appropriate education is the best way to promote safe cycling. I’ve been wearing my helmet a bit more lately…You seem to have a lot of experience on the subject (great posts on your blog, by the way). Any chance I can get you to write a guest post?

Lasesana, Thanks for your reply and I appreciate your invitation to write a guest post. Can you please e-mail me at to discuss privately? Many thanks!

The e-mail address was deleted from my reply. It is mpion (“at” sign) swbell.net. Thanks!

Excellent, well researched and written article. Thanks for presenting the subject in a balanced manner. A number of years ago the BMJ published a study that concluded injuries and deaths associated with cycling were more associated with years of cycling experience than with helmet use i.e. kids should wear them, expreienced adults not necessarily. Sometimes I do, sometimes I don’t.

Thank you for sharing that! Most people say they wear one ALL the time, yet half the people I see on the street every day are not wearing a helmet. I agree that kids should always wear helmets, though

This is an amazing overview of the debate over whether or not to wear a helmet. I wrote about it a little while ago, because, for a long time I never knew that there even was a debate about it and how deep it went. I am still unsure of what’s right, and maybe the is because there is no real right and wrong in this situation.

Like you said, maybe sometimes a helmet is the right choice, and on others you shouldn’t feel constrained to wear one.

I haven’t actually thought about this until I saw the numbers in this article, but if bicycle fatalities and injuries make up 2% of total traffic fatalities and injuries, that may actually be higher than the average, because I believe that total bicycle commuters in the U.S. makes up only about 1% of traffic. But, of course, these are difficult statistics to play around with, because not everyone who rides a bike is doing it as a commuter, and then of course some would not be counted who do it occasionally. But, something to think about.

Thanks for writing this!

Thank you for reading and for sharing your thoughts. I’ve had some trouble interpreting the stats myself. I’m actually going to look into that again after reading your comment, and will post back with my findings. Thanks again!

That’s great, can’t wait to hear what you find!

The debate can suck the energy out of cycling advocates, and serves as a red herring from big problem of safe cycling infrastructure, people who text while driving (even though several jurisdictions have laws that ban texting while driving) and driving culture of North Americans ie. big open spaces means impatience, driving faster, yaddyadddaaa.

I value my health and life so I wear a helmet. A minor concussion can be dangerous. I’ve fallen 3 times off my bike …on black ice in the winter and I was cycling slowly with hardly any cars around!

My partner knows a cycling lawyer in Vancouver BC who specializes in personal injuries involving cyclists. (Name is David Hays or Hayes.) I think he sees such unpleasant cases that it’s turned him off from tons of cycling around cars.